In Spring 2012, London-based documentary photographer Tamsin Green traveled to India and volunteered her time and skills to photograph the inspiring work of two Global Greengrants Fund projects. You can view more of the beautiful photos she took there and elsewhere on her website.

In Spring I visited two Global Greengrants Fund-supported rural communities in India, where local people are empowering communities through farming. Grassroots groups are increasing awareness of the dangers of pesticides and educating women, children and farmers on nutrition, sanitation and how to increase their access to food.

As a photographer my mission was to document the work that Global Greengrants Fund’s grantees are undertaking in this region and to try to tell the story of the inspiring people who are working together to improve their livelihoods.

Bidhichandrapur Chetana (BCC), Bidhichandrapur Village

Bidhichandrapur Chetana (BCC), Bidhichandrapur Village

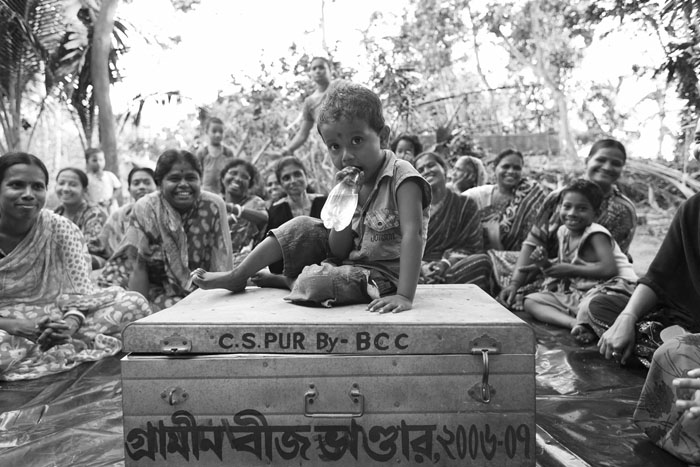

Bidhichandrapur is a small town nestling among mangrove trees in the tropical state of West Bengal. It is a community of agricultural workers, with a minority of labourers making the weekly commute to the states capital of Kolkata. Here, local organization Bidhichandrapur Chetana (BCC) is working with the villagers to create a more self-reliant community that will become free from illness, illiteracy and poverty. Their focus is on three core issues: womens’ empowerment, child education, and organic nutrition.

BCC seeks to empower women by giving them the tools they need to feed their families on homegrown quality organic vegetables. Fittingly, their motto is ‘Organic food gives me peace of mind’, and this can be found lovingly scrawled on walls throughout the village.

Education on methods of organic pesticide and healthier alternatives to conventional fertilisers is important to these people. The women have begun to cultivate their own gardens on modest plots of 5 to 20 square meters, growing a variety of crops, from carrots and beans to bananas. A successful nutritional garden provides the majority of fresh food that a family needs. The field and health workers of BCC make daily home visits to these gardens to offer education and support.

On a larger scale, BCC has successfully trialed SRI (System of Rice Intensification), an organic method of rice farming. The farmers manually spray the carefully spaced rows of rice plants with a homemade bio-fertiliser, made from tobacco, manure and weeds. Upon seeing the increased yield that these plots are producing, many neighboring farmers have begun to convert their own rice crops to the SRI method.

Meanwhile, a pre-school education centre teaches children about their environment from a young age. This next generation is engaged in building solar cookers, producing fertilisers, and learning how and why to grow their own food. BCC hopes that this will pave the way to a sustainable community in the future, one that is capable of being self-sufficient.

Malabika Datta Saha, Suapara Tribal Community

Malabika Datta Saha, Suapara Tribal Community

The displaced tribal community of Suapara is a matriarchal society. After Independence, such communities became prevalent throughout West Bengal, separate from the ‘normal’ caste society. The women here are agricultural workers and the breadwinners of the family.

Malabika Datta Saha is a local woman focused on educating the tribal community of Suapara to increase their ability to manage their natural resources and improve nutrition and sanitation. This is an extremely sensitive and challenging task as tribal communities are typically inward looking and are not open to education from outside.

The community in Suapara is a cluster of twenty or thirty dwellings along the banks of the river. As in Bidhichandrapur, the women here have been successful in establishing their own nutritional gardens to grow food for their families. The support from Global Greengrants Fund has enabled the construction of rice stores in order to separate farming activities from the family dwellings and improve sanitation. Some of the tribal farmers’ nutritional gardens have been successful enough to grow surplus crops that they can sell, enabling them to generate a small income. The women have made a great start in improving their livelihoods. and the ongoing education and support from Malabika will ensure these foundations continue to grow.

Shared Knowledge

Both BCC and Malabika cultivate the exchange of knowledge within their communities, thus forming strong units that are working together.

In Budhichandrapur, there are three women’s farming groups that meet once a month to discuss agricultural problems, find solutions and share knowledge. They manage a community seed bank, where seeds are deposited after harvest. The seeds are then exchanged by the women to diversify the crops they can grow in their own gardens.

The women spoke passionately about their sense of achievement in managing their own gardens, and they showed great creativity in overcoming obstacles. They also share a desire to think about the future and improve their livelihoods.

Water is the most urgent topic for many of these monthly meetings, either an abundance of water or shortage of water, each bringing its own challenges. The current low water level in local rivers and wells is typical in pre-monsoon season, making sourcing water for irrigation and daily usage problematic. During the monsoon the over abundance of water creates a very different problem.

It is April and in just a few months the entire village of Bidhichandrapur will be under 5 feet of water in a flood that will last for 2-3 weeks. This is a devastating yearly occurrence and the women now focus on how to cope during this season when there will be food shortages and they will have no way to make money. The government gives families rice for flood relief, but not enough to feed a family. When the water finally subsides they will discover that their painstakingly cultivated nutritional gardens will have been washed away.

The women are thinking proactively about how to speed up their recovery time, and as a short-term solution have begun to cultivate saplings for post-flood planting into their nutritional gardens. A longer-term solution is required that prevents this seasonal destruction of the community and their livelihoods.

These powerful networks are sparking a growing education on sustainable farming methods, increased awareness of the dangers of pesticides and improving nutrition in remote regions. The next step is to connect these and other like-minded communities to enable them to work together to affect change on a larger scale.

As my stay drew to a close, we took a break from filming to enjoy the festivities of Bengali New Year, an amazing visual spectacle. We watched young men of the village at the end of a long fasting period throw themselves from the top of a rickety platform onto a cloth supported by their fellow fasters. But not before bestowing blessed fruits on the children waiting below. The overflowing sense of community experienced in these gatherings, and the warmth with which I was welcomed into the homes and lives of these inspiring people was overwhelming. Of all the delicious Indian cuisine I sampled throughout my extensive travels in India, the home-cooked organic meals prepared by the women of Bidhichandrapur are the ones that I will always remember, as a symbol of a bright and very tasty future.