Words by Tatiana Rodríguez Maldonado of the Global Greengrants Fund Andes Advisory Board. Tatiana is a political scientist and a researcher on the environment, security, armed conflict, human rights and communication. She has worked in CENSAT Agua Viva – Friends of the Earth Colombia, as the coordinator of the Mining Area, supporting communities in the defense of their territories against extractive projects. She now works for the National Center for Historical Memory, coordinating the area that supports victims memory initiatives.

It’s hard to believe how immense the consequences of building a dam can be. The general opinion is that hydroelectric plants are clean energy and that this kind of project brings only benefits to the economy and the people. But nothing is farther from reality in the territories of Colombia where hydroelectric dams have been built.

On the one hand, there are several outcomes that used to be hidden or just understood as “side effects,” they didn’t always occur and were dismissed. But, at the root of it all, the changes in the lives of the population that lives near the rivers are very deep, usually irreversible, and the promised benefits never come. For them, the river is not simply a canal for the water, it is a body, it is a person with feelings, it represents life in community, family, fun, and love.

Everything takes place along the river, and knowing its dynamics is essential: from it you can understand the weather, you can recognize plant and animal species, you can tell the seasons, the moments of bountiful fish, and when the water will rise and fall. By understanding the river you know where and how to build your house, and you create specific manners to occupy the space and spend your time. The fishermen, for example, are kings and queens during the night because that’s the perfect moment to hunt, then they usually rest during the day, escaping from the harshest sun. While they fish, the moon is an appreciated friend – working alongside their families and colleagues, they use canoes and nets made by their own hands.

But not everything is positive, and the river can also remind you of painful things. During the armed conflict in Colombia, fishermen would find human bodies (or body parts) floating in the water. The brutal landscape was overwhelming, but they overcame it and felt obliged, as human beings, to take them out and bury the bodies in the riversides. They would think that maybe one day a family member or friend would come asking and they would find an answer to their prayers. Sadly, this scenario was more common than society would like to admit and today, and under the grey sand of almost every river in the country lies a missing person that will never be returned to their family.

In the state of Santander, in the northeastern part of Colombia, this kind of horror is mixed with the remembrance of the construction of the Hidrosogamoso dam, which began in 2009 and quickly became the main headache for the people who lived nearby. Their memories of this process are a thousand times more torturing than what they lived in the war. In their words, they feel that even the violence of the conflict, or the loss of a loved one, was less harmful. In the end, those who lost loved ones had the hope to survive, to continue and rebuild their everyday life, but for those facing the hydroelectric dam a giant wall existed and any hope for a future was lost, the sadness filling the atmosphere.

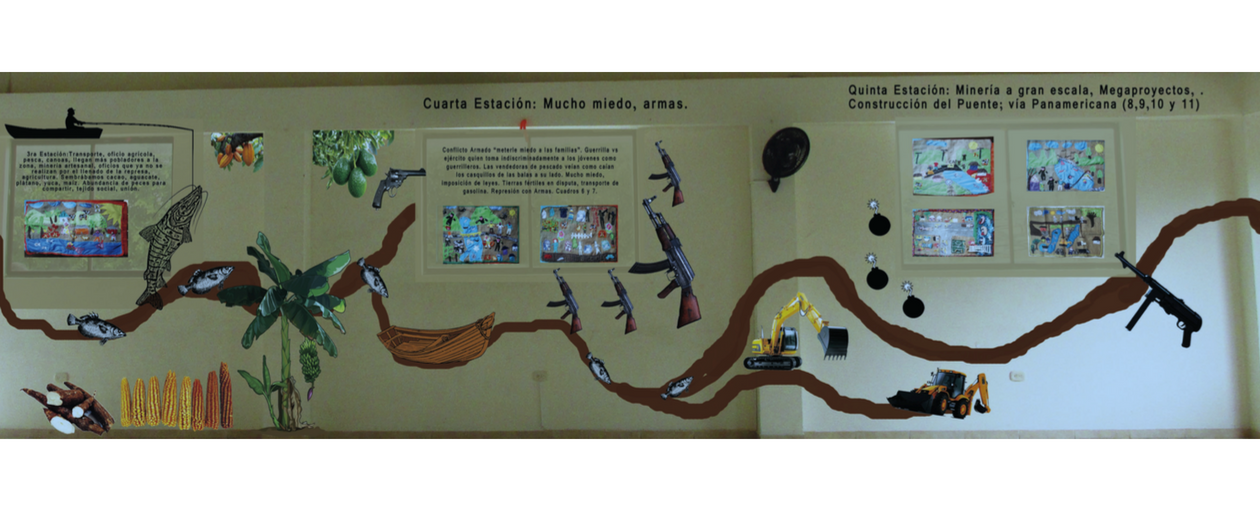

The good and the bad passes in the waves, but people don’t want to let it go just like that. Since they lost their ways of subsistence, women in the region started working on their own project, in an attempt to stay optimistic and pursue different ways to protect life in the community. Women of the Ríos Vivos Movement (the national anti-dam movement) took needle and thread and began to capture their memories on fabric with a knitting technique originally used for Violeta Parra during the Chilean dictatorship called “arpillería.” Without a clue in the beginning, the first results where insecure and the lack of experience was evident in their wounded fingers as well.

But the talent was there, waiting to see the light. After a few months, and with the support of Global Greengrants Fund, they created a whole gallery of artwork. With 20 pictures they told the world their experiences, through their own voices, with an incredibly expressive force. Women fishers and fish sellers are now proudly showing their knitting and traveling around Santander, and soon around the country, in a process that is giving life back to the rivers, and for people to feel again as natives in lands that they feel they know less and less like the one where they grew up. They say that the Sogamoso and Chucurí rivers in Santander, come back to life with every stitch of the arpilleras.

Photo credit: Rios Vivos Santander